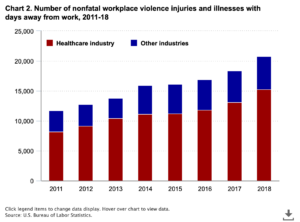

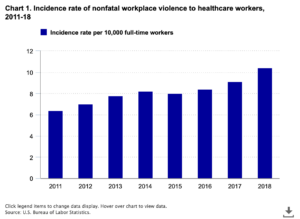

A study from the US Bureau of Labour Statistics shared that nonfatal workplace violence against healthcare professionals occurred at a rate of 10.4 per 10,000 workers in 2018. The rate the year before was 6.4 per 10,000. In 2018, the rate for all industries was only 2.1. Violence against healthcare workers appears to be on the rise.

A 2022 American College of Emergency Physicians poll of more than 30,000 emergency physicians found that witnessed emergency department violence was up 24% compared to a similar survey conducted in 2018.

To be clear, violence in healthcare is not just perpetrated against physicians. Shockingly, 60% of those who have experienced violence are bedside nurses. Healthcare workers’ risk of injury from workplace violence is five times greater than that of workers in other industries. That rate increased 63% from 2011 to 2018.

But it’s not surprising for nurses and physicians who have frequently experienced workplace violence. Therefore, how can we solve this issue? How can the healthcare sector help and support workers to ensure their safety? This blog will focus on workplace violence in healthcare, discussing the impacts and strategies the industry can make to ensure the safety of its workers.

Defining Workplace Violence

What is workplace violence?

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defines workplace violence as “the act or threat of violence directed toward persons at work or on duty, ranging from verbal abuse to physical assaults.” Other organizations broaden the definition of workplace violence to include acts of aggression, physical assault, or threatening behavior in the workplace that endangers customers, coworkers, or managers.

Despite differences in definition from one organization to the next, they have common themes. Ultimately, workplace violence in healthcare settings refers to various violent acts committed by patients, visitors, and employees/workers that cause actual physical harm or cause concern for personal safety.

Why are healthcare workers at risk from workplace violence?

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, healthcare workers accounted for nearly three-quarters (73%) of all nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses from violence since 2018—five times the rate of any other worker in another industry.

A new National Nurses United (NNU) survey found that more than 8 in 10 nurses saw or experienced workplace violence in the last year. Nearly half of respondents thought that violence had worsened in healthcare facilities in the previous year—an increase from a March 2021 NNU survey that found only 21.9% thought violence was increasing.

Surveying the Landscape: Insights from MDLinx Survey

A survey conducted by MDLinx, commissioned through M3 Global Research, sheds light on the impacts, root causes, and potential solutions to workplace violence against healthcare professionals. The survey, involving 50 practicing physicians, paints a stark picture of the challenges faced by those on the frontlines of care.

Authored by Shamard Charles, MD, MPH, their research article highlights the grim reality healthcare workers face. He mentions that in healthcare settings, violence against physicians and healthcare professionals is escalating, turning hospitals and clinics from sanctuaries to “danger zones.” This trend is alarming and deeply concerning for the well-being of healthcare workers, who are already under immense pressure.

Key Stats from the Research

- In a national poll conducted in 2022 by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and Marketing General Incorporated, more than 30,000 ACEP members shared their thoughts on workplace violence in the emergency department (ED). Responses from the 2022 survey (2,712) were compared with 2018 results.

- The report found a 24% increase in witnessed emergency department assaults in the four years (79% in 2022 compared with 55% in 2018).

- Moreover, roughly 85% of physicians reported a loss of productivity, increased anxiety, and emotional trauma from such assaults.

- Patients’ extreme behavior frequently causes workplace violence in healthcare. Because diagnoses vary and do not always result in aggressive behavior, the situations are unpredictable. Various factors, including pain, a dismal diagnosis, and disease progression, cause patient agitation. As a result, they act out, resulting in assaults and attacks on healthcare workers.

When healthcare workers witness these incidents, they are more likely to experience emotional distress, which may lead to their resignation. The organization will incur high turnover costs as a result of this. That doesn’t even consider the costs of those who miss work due to the violence.

So why don’t the healthcare workers report such violence and ask for greater security?

Lack of Reporting

Survey data highlights the underreporting of violent incidents in healthcare settings, even in facilities with formal reporting systems.

- According to a survey of over 4,700 Minnesota nurses, only about two-thirds of physical assaults (69%) and non-physical assaults (71%) were reported to a manager. Bullying and verbal abuse are more likely to go unreported than physical assaults.

- The GAO report noted, “Healthcare workers may not always report such incidents, and there is limited research on the issue, among other reasons.”

- Research has found that only 20 to 60 percent of nurses report incidents of violence.

According to the ANA position statement on incivility, bullying, and workplace violence, to address a problem, one must first understand its full scope. As a result, to address violence in healthcare, notably among Registered Nurses, the causes of underreporting must be identified and addressed. A systematic reporting mechanism is required because workplace violence is difficult to prove with physical evidence.

Reasons for Underreporting

The absence of reporting is a significant impediment to effective research and regulatory or legal action. Here are some common reasons for not reporting violent incidents:

- A healthcare culture that accepts workplace violence as part of the job.

- A widespread belief that violent occurrences are commonplace.

- A lack of consensus on definitions of violence; for example, does it encompass verbal harassment?

- A fear of being accused of poor performance or blamed for the occurrence, as well as of reprisal by the perpetrator and employer.

- Inadequate understanding of the reporting mechanism.

- A belief that reporting will not affect current processes or reduce the likelihood of future occurrences of violence.

- A belief that the event was not severe enough to warrant reporting.

- The practice of not reporting unintended violence, such as situations involving people living with Alzheimer’s.

- Lack of Manager and Employer support.

- Lack of training on reporting and handling workplace violence.

- Fear of reporting supervisory workplace violence.

- The lack of underreporting is unlikely to force any change.

When considered together, these obstacles provide significant disincentives for Registered nurses to report workplace violence incidents. A holistic strategy can help overcome these obstacles and create cooperation between Registered Nurses and their employers.

What Healthcare Professionals Have to say:

What triggers violence against HCPs?

The triggers for workplace violence are layered and multifactorial.

Nyema Woart, DO, an emergency medicine doctor at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, New York, says the alarming rise in workplace violence, particularly in the ED, is concerning and believes socioeconomic stress, patient proximity, and many other factors are to blame.

“The ED isn’t safe for doctors. There are few, if any, barriers between patients and providers, so we’re constantly in harm’s way. “

— Nyema Woart, DO, emergency medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, New York

“Long wait times and a lack of resources have made it hard to take care of patients, especially when they have high demands and want things done a certain way,” Dr. Woart adds. “Their stress plus the high acuity of the ED means patients sometimes misconstrue what we can do, and how quickly we can do it, for them. When their expectations are not met, it leads to frustration, which they sometimes take out on providers.”

But these factors don’t tell the whole story, Dr. Woart says.

Patients enter hospitals and clinics with economic, relational, and professional issues compounded by poor health. The combination of outside stressors, pain, fear, and undiagnosed medical or psychiatric conditions heightens patient-provider tensions, creating a complex mix of feelings that may be difficult to navigate.

According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, frustration amid staffing shortages, substance abuse, grief for a declining loved one, racial or ethnic prejudice, and dissatisfaction with a provider—especially those who adhere to stricter prescription guidelines for controlled substances—are among the most common reasons why patients resort to violence.

Quotes from other Healthcare Professionals:

- “I think it reflects an increase in violence everywhere in every sector of US society. We value guns and are an aggressive society. We watch it on TV, in the movies, and we are more divided than ever.”

- “Patients suffer from many mental health disorders. They have substance abuse disorders and PTSD from emotional, sexual, and physical abuse. Violence is associated with all of these experiences.”

- “There are several issues: Poor doctor-patient communication, overburdened healthcare system, inadequate security measures, lack of respect for healthcare professionals, and political and social unrest.”

- “Patients have increased financial burdens, and their care is not always covered by their insurance so they displace their anger onto healthcare professionals.”

- “False information about the COVID-19 origin and the dangers of the vaccination has resulted in mistrust of healthcare professionals.”

Add to this the lingering tensions between patients and providers, which were unmasked during the pandemic, and you have the makings of an explosive situation.

“Widening income gaps from the pandemic added fuel to fire.”

— Nyema Woart, DO, emergency medicine, The Brooklyn Hospital Center, New York

“We [society] have to unpack the root causes of these events, while also assessing the physical, emotional, and psychological toll it’s taken on providers, and their ability to provide quality patient care,” says Dr. Woart.

Preventing Workplace Violence

Using the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s strategy

Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) workplace violence prevention program is designed to:

- Improve the working conditions and quality of the working environment.

- Eliminate or minimize potential physical or psychological injuries.

- Limit financial losses for employers and employees both

- Ensure that the organization follows and upholds institutional workplace violence prevention programs.

Most states require healthcare facilities to develop violence prevention plans; guidelines are available. OSHA advises developing a program that includes the five essential aspects listed below:

Management Commitment and Employee Participation

Recognizing workplace violence as a safety and health threat is a critical first step toward successful management leadership. Managers of healthcare facilities can show their commitment to reducing workplace violence by:

- Creating violence prevention programs with well-defined aims and objectives.

- Providing appropriate funding for the program.

- Appointing leaders who have received adequate training to facilitate the program.

- Providing continuing assistance to guarantee the program’s success.

All program phases should include employees (who have firsthand knowledge of workplace difficulties). They should be encouraged to report concerns and offer feedback without fear of retaliation.

Workplace Analysis and Hazard Identification

Following an initial workplace study to identify risks and hazards, management should create policies and processes for the ongoing identification of workplace hazards and risks and perform periodic reassessments and evaluations.

Hazard Prevention and Control

Management should develop measures to remove workplace dangers and strive toward the goals and objectives specified in their violence prevention program.

Safety and Health Training

Train employees to recognize dangers and respond appropriately to aggressive conduct displayed by patients/clients, visitors, coworkers, and others. They should know what to do in an emergency (e.g., active shooter, natural catastrophe, etc.) and where and how to report problems/hazards.

Record Keeping and Program Evaluation

A critical component of workplace violence prevention programs is accurate and complete documentation. Facility managers should keep records of dangers, assaults, injuries, illnesses, remedial measures, and staff training. This can assist employers in identifying patterns and trends and developing solutions to recurring problems.

Including these aspects in a violence prevention program takes time and organizational support. It is critical for every healthcare professional working for an institution that lacks a comprehensive program to demand change. However, another option is available if any employee hesitates to quit the firm and is prepared to battle this matter.

Workplace Prevention Strategies for Nurses

Actively engage in your facility.

According to OSHA, employee engagement is critical to the success of any workplace violence prevention program. They suggest that nurses accomplish the following if possible:

- Learn about the company’s workplace violence prevention program and procedures.

- Participate in the organization’s safety training programs.

- Participate in committees for safety, health, and security.

- Participate in employee grievance or suggestion procedures.

- Report violent situations as soon as possible and as precisely as possible.

Dress for safety

The way healthcare workers dress can assist in increasing their safety. NIOSH suggests:

- Removing anything that may be used as a weapon or stolen

- Hair should be held back so it cannot be readily pulled out.

- Avoid wearing earrings or necklaces that can be pulled.

- Wear clothing that isn’t too big or too little; too big clothing might get snagged on anything, while too small clothing can hinder movement.

- Use breakaway safety cords or lanyards for name tags, keys, and other small items.

- Be conscious of your work environment.

- Knowing our surroundings, like any other area we visit, may significantly increase our safety.

- Be mindful of static (room arrangement, doors, lights, and workstations) and changeable (weather, noise, and personnel levels) threats.

- Be conscious of your work environment.

- Knowing our surroundings, like any other area we visit, may significantly increase our safety.

- Be mindful of static (room arrangement, doors, lights, and workstations) and changeable (weather, noise levels, and personnel levels) threats.

NIOSH specifically advises healthcare personnel to be cautious of the following:

- When switching workplaces, take note of exits and emergency phone numbers.

- Confusion, background sounds, and congestion can increase stress levels.

- Disruptive behavior peaks during meal times, shift changes, and patient transportation.

Be aware of patient behavior.

- Because patients are responsible for an estimated 80% of violence against nurses, being aware of patient behavior that might lead to violence is crucial.

The following are some probable symptoms of violence:

- Verbal cues.

- Screaming or speaking loudly

- Threatening tone

- Nonverbal signals and behavioral cues.

- Physical characteristics (neglected clothing, hygiene)

- Arms crossed across the chest.

- Fists clenched

- Excessive breathing

- Agitation, pacing

- A terrified expression denotes dread or severe anxiety.

- A fixed gaze

- Pose that is aggressive or menacing.

- Hurling items

- Intoxication: Indicated by sudden changes in behavior (alcohol or drugs)

Awareness is key.

Being conscious of our sentiments and reactions to various events might impact the result. NIOSH suggests that you pay attention to your intuition. For example, a “fight or flight” reaction might be an early warning indication of impending danger and a signal to seek assistance or flee.

NIOSH also advises being conscious of one’s own body. Overtiredness can significantly impact how one responds to a complex scenario.

Check your socio-cultural biases.

Recognizing how our cultural background influences how we perceive the world is another vital part of self-awareness. These perspectives can control how we respond to patients and coworkers and how they respond to us.

According to NIOSH, misconceptions caused by language limitations, for example, might escalate a patient’s anxiety to the point where violent attacks are their only method to express dissatisfaction or suffering.

Use violence risk assessment tools.

Healthcare organizations can examine individuals using violence risk assessment instruments. These tools offer healthcare workers a consistent frame of reference and knowledge, reducing the possibility of misinterpreting a person’s capacity for violence.

NIOSH cites three examples:

- Triage Tool: used to assess a patient’s potential risk to others or themselves.

- Indicator of Violent Behavior: A list of five observable behaviors that suggest risk to others.

- Danger Assessment Tool: This tool assesses the danger of an individual demonstrating possibly aggressive behavior to nurses and other workers.

Safety in non-institutional healthcare settings

Healthcare organizations are responsible for establishing safeguards for employees working outside the hospital, such as in-home care settings.

For non-institutional healthcare settings, NIOSH recommends the following safety checklist:

- Examine agency files to perform a background check on the patient.

- Examine whether a patient’s family member has a history of violence or arrest.

- Suppose you enter a situation already classified as potentially dangerous over the phone. In that case, you should be accompanied by a team member who will provide de-escalation and crisis intervention training.

- Always keep a mobile phone on hand.

- Make sure that someone knows where you are.

A Comprehensive Violence Prevention Program for the Win

“Two steps forward, one step back is still one step forward”

Rosa Diaz, Brooklyn Nine-Nine

Workplace violence is a serious problem worldwide, particularly in the healthcare industry. Patients who are ill usually become irritated and act out in a medical setting.

Reducing workplace violence protects patients and caregivers, improves patient outcomes, produces a more comfortable work atmosphere, decreases staff turnover, and saves healthcare institutions and, by extension, taxpayers money.

Registered nurses, other healthcare employees, and their employers must participate in creating, implementing, and improving workplace violence prevention programs and adequately responding to their aftermath. Employee and employer participation is vital to the success of any workplace violence prevention program. Only by taking these actions will Registered Nurses be able to address the issue of workplace violence.